Every Possible Disclaimer: This incident is true, and the dispatchers and patient are real. The details are a composite hash of the five (5) sites where I’ve served as a medical interpreter. As always, the characters have pseudonyms. The fictitious name “Nikolai Petrov” is something like a Russian “John Doe”; the world has countless real Nikolai Petrovs, and this character is none of them.

Life as an interpreter was blissfully easy compared to the jobs of so many healthcare workers who face disrespect and harassment at work, some of it dangerous. My wartime-era former-Soviet seniors were the least stressful clientele in the hospital. The interpreter setting has evolved far from the quaint setting described here. Now the service employs telephonic remote personnel, with instant access to many languages. That leaves the question: What about the companionship of the in-person interpreter, someone who might know the whole family for years, someone to accompany the patient from clinic to clinic all day or stay at the bedside all night on what might be the hardest day of their lives? That was a human connection that many hospitals can no longer afford.

This story is not in any way a criticism of our patients, or of any culture group. It is about holding off on judgment until I know a person’s back story, and why he might behave the way he does. This piece was prepared for last Valentine’s Day, and took one year to finish. Chances are, in the next few days other improvements will come to mind. The story might read better a week from now. -mary

7:25 am. I got to Base, dropped my bags, and got my schedule from the mailbox.

Dispatcher Delia hit Pause on the voicemail cassette recorder. She lowered her headset microphone, and tapped Speak/Listen on the telephone console. “Interpreting, what language?” She waved at me to stop. “For Pre-Surgery, and Creole as in…? Well no, Creole is not a language, it’s — No Dr. Marsden, I am not trying to insult anyone’s culture, I only – Look. Your patient arrived from…? Haiti. Haitian then. Not one of our languages. But call…” She checked a Rolodex card “555-1234. Ask for André Etienne in Engineering. Why Engineering? Mr. Etienne is an engineer. Loop him in with the patient and the OR. Best we can do welcome bye.”

“Mary!” Delia hit Disconnect on the console, and raised her microphone. “Change for your 3:00 Radiology.” She opened the appointment book, an atlas-sized hourly calendar with two foldout double pages for each day. She erased and rewrote a note, then flipped the page to check and make sure the eraser didn’t wear through to notes on the other side. “It’s now Cardiology.”

“Okay.” I handed her my schedule. “Who’s on for Radiology then? Rodion is off at 1:00.”

“Zoya’s got it.” Delia hit Speak/Listen and lowered her microphone. “Interpreting, what lang — Oliver? Yes you are marked right here in the book. 7:40 for PT. Didn’t expect you? Lemme call Trixie bye…. Hello Interpreting what language? No Trixie, Oliver is not late. He is waiting for your patient, in your exam room, signed in by your staff. Right.” Disconnect. “Jeez…”

She raised her microphone, corrected my schedule, and handed it to me. “Ah! First day back…”

“We missed you.” I took back my printout. “Nice vacation? You so deserved it.”

“Heavenly. Had to take the time. Use it or lose it.” She winked. “Ya know how that goes.”

“Oh Sure.” I gave her an upbeat smile. “Sure.”

She hit Speak/Listen. “Interpreting, what lang– STOP WHAT LANGUAGE? YES PLEASE WAIT.” She hit Hold and raised her microphone and her voice. “Hannah! Line 3 urgent.”

“What am I now?” Hannah called from the next room. “Vietnamese again?”

“Vietnamese was on Line 4; Line 3 incoming is Chinese. Thanks Hon. Transferring.”

“Guys!” Fernanda from Admissions burst in. “Answer your phones! Everybody’s dialing us instead.” She slapped down a stack of pink memo slips on our message spike.

“I owe you, Fernanda.” Delia opened the first aid kit for a small bottle. “Cassette tape ran out.”

“Ran out?” I asked. “That’s a 90 minute tape.”

“Cody didn’t erase the voicemails. No one told her to delete once they’re done.”

“Oh dear.” Cody was our smart cheerful high school volunteer. She came to our rescue covering two days of Delia’s vacation. Now the dispatchers had 90 minutes of messages that were either returned or not, confirmations called in or not, appointment requests booked or not, and six phone lines of Monday calls incoming.

“Interpreting, what — Sí, lo sabemos.” Delia popped open the small bottle and shook out two pills. “Su intérprete será Nina Elena. En cinco minutos. De nada adiós.“

“Mr. Wang died!!” Hannah looked in. “And due in Surgery followup, 10:00 Tuesday.”

“Which Wang please?” Delia flipped up the mike and opened the book to Tuesday.

“Wang Shan. Scotty,” said Hannah. “That was his wife on Line 3.”

“Not Scotty? Oh Hannah. I’m sorry. Call May Li. Gimme her schedule a sec.” Delia erased Mr. Wang’s Tuesday for Surgery, crossed him out on May Li ‘s timesheet, and gave the printout back to Hannah. “Interpreting, what language? Labor & Delivery? Right. How far along is she? Which dialect? Okay paging Jenna bye.” Delia typed a pager message.

Pleasant chime sounds floated from the ceiling. “Code Red,” said a soothing male voice. “Facilities Level 4. Code Red. Facilities Level 4.”

Delia read through Fernanda’s stack of pink slips, and rearranged their order on the spike. “So Mary. Your 3:00 Cardio is Nikolai Petrov. Have you worked with him before?”

“No.” I put on my hospital lanyard and ID badge. “What’s he in for?”

“Routine monthly pacemaker check. Hold on. Interpreting, what language? Hey Cokie. The patient told you what? Well you tell him that Yes Renala is a female, she is our only speaker, she will keep it confidential, and his male provider will keep him safe, chaperoned, and draped behind a curtain.” Delia pointed an imaginary finger gun to her head. “You’re a trooper, Cokie.”

“Coffee cart.” Hannah popped in. “Here’s your Earl Grey. With milk, right?”

“Or vodka.” Delia took the two pills with her tea. “Whattaya want, Ross?”

“Yo!” Ross from Transport waved an envelope at us. “Mindy’s pizza sendoff, 1:00. You in?”

“Interpreting, what — Jenna! L & D stat! Thanks luv.” Delia handed Ross five dollars and glanced over at me. “So Mary. Your Cardio…”

“Something about Petrov?” I asked her.

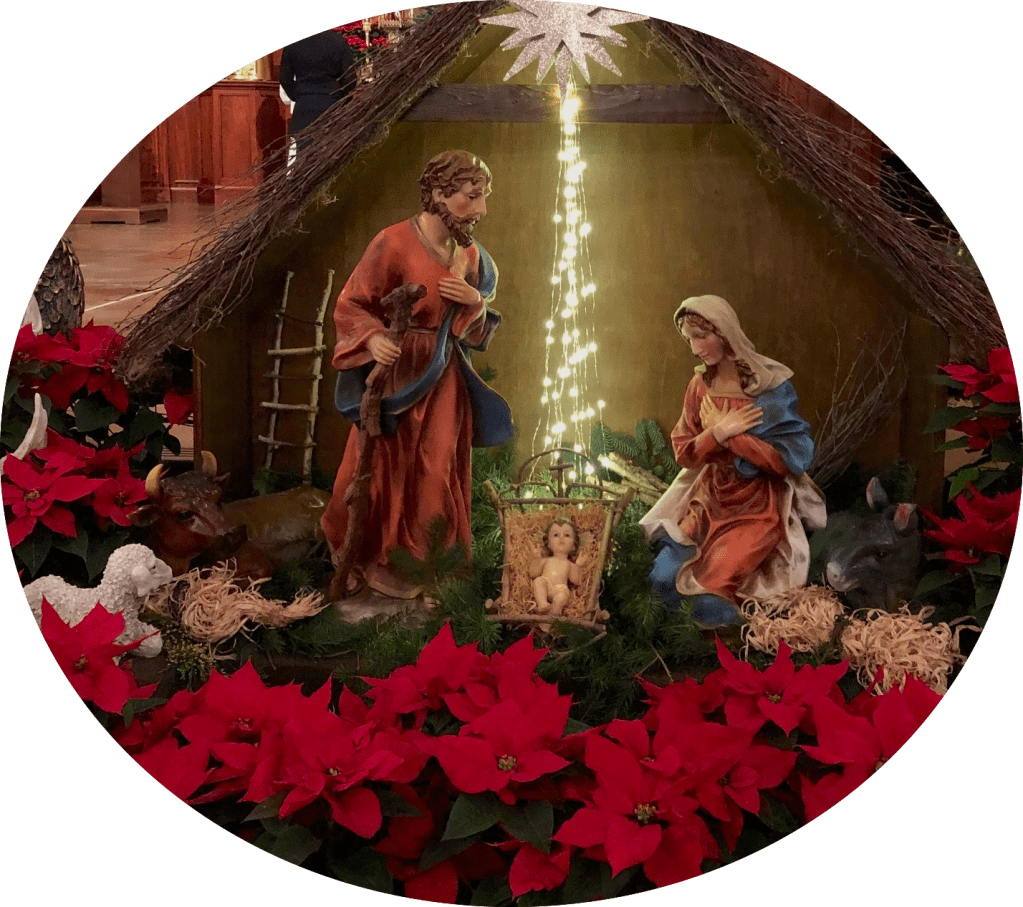

“Right. Lovely man. Interesting life story, and he’ll tell you all about it. Watch for him at the side door. He and his wife Lilya come from Pineview Manor. They walk uphill from the bus stop hand in hand. When she’s up for it, she comes with him to check on their heart. As they call it.”

“‘Their’ heart?” I looked up from the schedule. “Joint appointment?”

“No. Lilya’s not our patient. We don’t follow her care.” Delia gestured a confidentiality zipper at her lips. “‘Their’ heart because they’re inseparable lovebirds. Cardio is their big monthly date. He’ll buy her a red rose in the Gift Shop after. Especially today.”

“Today.” I checked the date on the schedule. “Fourteenth?”

“‘Fourteenth,’ she says. It’s Valentine’s Day, hello. Lane’s taking me to the same cafe where we had our first date!” Delia beamed at me. “How ’bout you? Big romantic plans for the holiday?”

“You bet!” I added more oxygen to my smile, with a little fist sideswipe to convey a can-do spirit. “The big plan is Petrovs in Cardio, and their valentine heart.”

“Code Red resolved.” More chimes from the ceiling. “Code Red all clear.”

“They really are the dearest lil’ lovebirds. Nikolai adores his Lilya. And, he will still flirt outrageously with every female on staff. Including you. Enjoy!”

“Right.” I took a deep breath, squared my shoulders, and picked up my bags.

_______

2:30 pm. After one audio check, one orthotic fitting, one sed rate blood test, one ultrasound, and one colonoscopy, I signed out with the staff in GI Diseases and dashed through the parking garage, sprinting around the campus to the side drive. At 2:40 (Interpreter Rule: be prompt) I was at my post on the hilltop in good time. I caught my breath, and set down my bags.

Those bags were packed with care. Interpreter Rule: carry proper items for professional readiness in any situation. The large duffle held a tissue box, hand sanitizer, distance eyeglasses, a Russian-Russian medical dictionary, an English-Russian encyclopedia of medical phrases, laminated anatomical charts, bilingual Patient Q&As with drawings for inpatient staff, spiral notebook and pen, clinic phone directory, business cards for the various language voicemail lines back at Base, and my proud new interpreting certificate from the state Department of Health in an acetate page protector. The knapsack had winter boots, a sweatshirt, scarf, high-visibility vest and flashlight for the two-mile walk home, and a rain tarp for an ice storm on the way. The lunch bag was packed with a water jar, lentil patties, apple, banana, and almonds for a lunch that didn’t happen.

2:45. Hm. No couples strolling hand in hand; I ran two blocks downhill to check the bus stop.

2:50. My pager buzzed with a text alert from Base: Pt @ Reception. U? GO! The Petrovs? At Reception? I ran two blocks back up the hill and around to the main drive.

At the entrance, Mr. Levitskii was arriving at the kidney infusion center with his sit-down walker and oxygen tank. He whistled at me, slapping his knee. “Polkán! Idí, Polkán! Fido! C’mere, Fido!” He greeted all of us Russian interpreters that way. That was his light-hearted tribute for how he saw us tossed around with every phone call and pager alert.

“K vashim uslúgam! At your service,” I called back, giving him a snappy salute. In the hospital lobby I charged up to Reception Dotty at Visitor Information.

“Interpreter, you’re late!” said Dotty. “Pineview Manor sent your patient in their shuttle. He’s been waiting over a quarter of an hour for you.”

“A Vy guliát’ poshlí? Gone strolling?” Mr. Nikolai Petrov was eyeing my arrival. He was a distinguished Greatest Generation figure, standing tall and straight in a dress shirt, suit slacks, and a tweed jacket. His vigorous stance, thick silver hair, and blazing blue eyes called to mind Paul Bragg, a health enthusiast born in 1895, whose books had fans in both Russia and America.

“Zdrávstvuyte, Hello, Mr. Petrov. Interpreter Mary, for your 3:00 Cardiology.”

“So I heard. We have been waiting for you.” He looked me up and down.

“Yes, I’m sorry.” Keenly aware of the contrast between his dapper alert appearance and my perspiring breathless state, I looked around anxiously for Mrs. Lilya Petrova. Was she in the rest room? At the Gift Shop, buying a rose? “Are we waiting for –”

“Dlia Vas.” He cut me off. “I tól’ko dlia Vas. You, and only for you. It is now 3 minutes before the hour. Shall we adjourn already?” He flicked a hand to whisk me toward the Cardio suite. There Patient Coordinator Stella signed my schedule. “This way, Interpreter.” She rushed us to a room at the very end of the hall, closing the door as she left.

Squeezing past Mr. Petrov’s knees, ducking my head in apology for crowding him, I tiptoed to the door and eased it open again by six inches. Interpreter Rule: keep door open by a hands’ breadth. The open door policy was a standard best practice, a discreet signal that the patient was still in the room; otherwise, overworked staff had been known to forget that my elderly Medicaid patients on routine checkups were waiting, and we could be overlooked entirely.

Mr. Petrov hung a leather shoulder bag behind the door, and reaching in pulled out a plastic box.

“How are you today, Mr. Petrov?” I sat down.

“Fine. Never better.”

“Are we here for your pacemaker check?”

“Today is the fourteenth. Pacemaker checks are the first of the month.” He smiled. “You could learn that yourself if you looked at the patient chart before showing up.”

“Well, it’s a good thing we’re in the right place.” Interpreter Rule: Never access patient charts unless ordered to do so. “So we can tell the team all about it right now.”

Medical Assistant Cassie knocked and entered. “Name and date of birth?”

“Imia, famíliya?” I repeated for Mr. Petrov. “Dáta rozhdéniia?”

“Ia sam! I myself.” He waved my words away, and in English gave his name and birth date.

“And how are you feeling today?” Cassie logged in to the computer.

“Kák vy sebiá…?” I began.

“FINE!” Our patient sat tall, striking his chest with his fist. Opening the plastic box he took out his pill bottles, lining them up across the desk.

Cassie checked each prescription against his computer medication list. She applied a blood pressure cuff, pumped the bulb, watched the dial, and entered the reading. She locked the screen, left the room, and closed the door behind her. I got up and opened it again.

“Clogs?” Mr. Petrov put the prescriptions in their box. “For a medical setting?”

“Clog shoes are useful.” I was loyal to my rubber-grip footwear for running in the rain between clinics and for race-walking over polished floors. “Not the style in Russia, are they?”

“Oh, they are,” he assured me. “For slopping hogs.”

He sprang up and strode across the room, put the pill case back in its leather bag, and hung the bag back on the door. “Zhal,’ Such a pity. That you had to travel so far to work with me.”

“Far? Nichevó. No, no trouble,” I assured him. “I live close by.”

“Not likely.” He sat down again. “In this neighborhood there are no residential homes.”

“It’s campus housing. Studio room with shared kitchen.” I rather liked letting the patients know that not all Americans were drowning in wealth. My economy housing often led our Russians to reminiscences of life back in their Soviet communal apartments.

Nurse Keller charged into the room and logged in. She measured his blood pressure, measured it again, listened to his heart, then paged through the screens of his chart. “Mr. Petrov.” She swiveled to face him. “Merenice called this morning from Pineview Manor. She said they were sending you in on their shuttle, and that you woke up anxious and agitated. Any reason?”

“No. I am good,” Mr. Petrov quipped in English. From across the room his keen eyes monitored the green blinking cursor as she checked his record. “I am always good.”

She logged out, left, and firmly closed the door.

“One studio room.” Mr. Petrov gave me an appraising glance. “For you and your parents?”

” No, my parents live on their own. Out of state.”

“Why not live in their house, and care for them?”

“Oh, they don’t want or need care. They’re doing quite well.”

“Buy a house for them here. To live with you.” His bright blue eyes narrowed.

“They are fond of their own home and town, among their friends and activities.” Behind my smile I wilted a little. The mortgage officer at our bank had already let me know: with an interpreter salary and an on-call job, a mortgage was not in the cards. My lifelong dream of a family and home and a bit of land was receding farther every year. I sidled past Mr. Petrov again to open the door.

“Interpreting must have called you at short notice,” he commented.

“No, Delia is very efficient. She told me early, when I arrived at 7:30.”

“Yet you still showed up late and in a rush. You had trouble finding your own patient.”

“Thanks to Dotty in Reception,” I said brightly, “It all worked out. And here we are.”

This was a fairly typical first-acquaintance conversation. Interpreters for all the language groups faced personal questions and commentary. After all, most of our patients had lost their homeland, livelihood, professional identity, relatives and friends, social connections and familiar customs. Almost all of my Russian elder patients had depression, anxiety, memory issues, and several metabolic illnesses. They talked with nostalgia about their young days in Soviet times, when their fitness and knowledge were always in demand in war and peace. My patients did not choose America; they were uprooted and brought along by children and grandchildren. For them, exam rooms were a social gathering place. The interpreter was their American cultural informant, one who spoke their language. No wonder our personal appearance, ethnic and religious background, housing, income, relationships, and lifestyles were all a source of interest, entertainment, and gossip with countrymen.

Interpreter Rule: when a conversation takes an awkward turn, excuse yourself and explain that you need to answer a pager message. Fortunately, at that moment my pager buzzed again. Update? Needed ENT.

“Mr. Petrov, please excuse me a moment. I need to telephone my dispatcher.” I stepped into the hallway. Interpreter Rule: Never discuss an appointment in the patient’s presence. Besides, our small room had no desk phone, and clinics had no flip-phone reception. I headed up the empty hall to the clinic house phone and called Base.

“Interpreting, what language?” said Delia.

“Hello, Mary in Cardio.”

“Still??? Why are you just sitting around there? It’s a routine pacemaker check!”

“Yes, I was just going to call you.” Interpreter Rule: In any minutes of down time, always call Base; chances are they will send you to a filler appointment at another clinic.

“Olga and her daughter Sveta just showed up at Ear Nose & Throat. ENT expected them yesterday for Olga’s surgery followup, but they’re here now. How fast will you wrap up there?”

“They haven’t told me anything.” Olga and Sveta needed double interpreting; we used Russian-English for Sveta, who repeated everything to Olga in Russian Sign Language.

“Ok, I’ll send Polina. Get over to ENT and spell her as soon as you’re done.”

“Will do.” With double interpreting taking twice the visit time, ENT would not be happy waiting for me. At the same time, in Cardiology and other high-caliber clinics it was hard to coordinate provider teams and unexpected events. Wait times were much harder to predict. I glanced around the hall, and lowered my voice to almost a whisper. “This doesn’t look like a routine check so far.”

“Interpreter!” Nurse Keller appeared. “No medical discussion in the hall. Off the phone.”

“Yes, Ma’am.” I headed back to the room, leaving the door cracked open.

Mr. Petrov sat with folded arms, tapping his foot. “I thought you wandered off and left me.”

“Oh no,” I smiled at him. “Just talking to the dispatcher. I’m staying right here with you.”

“You must be new here. You haven’t had time to get a proper badge.”

“Badge?” Interpreter Rule: ID must always be worn in clinic. Startled, I checked my lanyard. “Why, here is my badge.”

“That’s not a proper badge with your real name.”

“The Security office issued this badge. Here is my real name.”

“It is not,” he insisted. “In English, suffix “-y” forms the diminutive: Micky, Bobby, Betty. Names for schoolchildren and movie gangsters. ‘Mary’ is not your real name.”

“But… Mary is a traditional Catholic name.” My devout mother often reminisced fondly of her love for the Blessed Mother, and her wish to give the name to me. “For the mother of Jesus.”

“Really now.” He rolled his eyes. “Her real name was Maria. And so is yours.”

“Her real name was Mariam.” No one had ever questioned my Mother’s baptismal name for me before My voice came out with the hint of an edge, breaking the Interpreter Rule: Never engage in disputes with a patient. A contractor who answers back will not be called to work again.

“My my.” His eyes gleamed. “Whatever you say.”

Two new providers hurried in with an EKG equipment cart. There was no curtain in the room, and not enough space for the furniture and equipment and four people. So to Mr. Petrov’s obvious amusement as he unbuttoned his shirt I averted my eyes and finally stood up with my face to the corner, ready to interpret the procedure. But the exam was administered in silence. One provider whisked the cart away while the other entered some chart notes and closed the door behind her. Mr. Petrov straightened out his jacket and shirt.

I stood up and eased the door open. “Mr. Petrov, I’ll be working right here in the doorway,” I explained, opening my vocabulary binder. Interpreter Rule: During down time, check translations of English-Russian patient education materials to make use of billable minutes.

“Interpreter.” Patient Coordinator Stella stepped in. “We’ll need you here tomorrow, 8:00 to noon for testing.”

“Tomorrow morning is Rodion,” I told her, “Rodion has seniority for morning slots.” Rodion was permanent, on salary. He had first choice of morning appointments, so he could pick up his wife and children in the afternoons.

“I asked you, Interpreter! For Mr. Petrov’s continuity of care.”

“You’re welcome to call Base. They determine the assignments.”

“Then call Base now and tell them we booked you for tomorrow.”

“Base won’t accept that second-hand. For billing, Maura needs to hear directly from the clinic.”

“I’ll tell them you refused, while I’m at it.” She closed the door.

“Well now.” Mr. Petrov turned to me. “You must have read great works of literature by our many stellar writers — Dostoevsky, Tolstoy, Chekhov. Which literary work is your favorite?”

“Rákovyi Kórpus.” I didn’t have to think twice. “Cancer Ward. Aleksandr Sol’zhenitsyn.”

“Rákovyi Kórpus.” Mr. Petrov raised a brow. “I said ‘literature.’ By an actual writer.”

“Yes. Rákovyi Kórpus is my very favorite Russian novel.”

“A story about a ward of hospital patients? Whining about their symptoms! That’s your idea of a literary book?”

“It’s my idea of a profound book.” I blushed. “One which is personally meaningful to me.”

“Ha.” He tossed his head. “Na vkus i tsvet továrishchei net. There’s no accounting for taste.”

“Kázhetsia.” I gave him a placating laugh. “Seems so.”

My pager buzzed: Stay after 5?

“Mr. Petrov, I’ll need to answer this message,” I apologized. Checking both ways for Nurse Keller, I headed back down to the hall phone.

“Interpreting what language.” This was now the cool no-nonsense voice of Dispatcher Maura.

“Mary, Cardio. Yes, can stay after 5:00. Did they tell you how long I’ll be here?”

“They’ve paged the attending; Schmidt is on his way. Something’s shaking at Cardiology. Some chain of command issue. Charge nurse wants Petrov admitted; but they don’t have the data to back that up. Sit tight there.” Click.

I went back to the little room, leaving the door open. “Mr. Petrov, I hear you have an interesting life story. Perhaps there will be time for you to tell me some of it?”

And at that, we were finally on safe ground. Mr. Petrov needed no further encouragement. He launched into his very own exciting history, well-polished with retelling and rich with long-term memory. After the War he’d been selected for special training that demanded technical expertise, extreme physical endurance, reflexes, and bravery. Now he expanded upon the successes of his team of men on missions that promised glory, patriotic pride, excitement, and inevitable injury or death. Somehow, Mr. Petrov and his close circle of comrades had all survived unharmed.

A gray-haired provider in a suit strode in with no badge, no introduction, and not a glance at us. His distinguished appearance and cut-to-chase manner suggested that this was attending Cardiologist Schmidt himself. He logged in to the computer and reviewed the chart. “A well-appearing white male, X years of age,” he announced. Speaking in a clear projected voice he adjusted a wired attachment clipped to his front pocket. “Referred by care home for uncharacteristic anxious and irritated behavior. Initial workup indicates…” He expounded upon technical details of the patient’s vital statistics and EKG, reached in the pocket to click settings on a recording device, and walked out closing the door.

Mr. Petrov turned to me for an explanation. I didn’t have one.

Despite my training, Schmidt’s rapid-fire narrative was technically incomprehensible; perhaps it was meant to be. At least for this situation we were covered by our Interpreter Rule: interpret only what the provider says directly to the patient, and what the patient says directly to the provider. In this case, there was nothing for me to say.

“Well. About your story.” I turned the subject back. “It really is remarkable.”

“I’m the only one of the team left alive. Last time we met was at Leningrad State University.”

“LSU?” I exclaimed. “I studied there. Summer, 1978.”

“1978 was the 35th anniversary of our mission.” Mr. Petrov’s eyes flashed brighter. “Our team leader was an LSU administrator.” With fond reminiscence he mentioned the team leader’s name.

“Administrator??” The name was striking and distinctive, drawn from several Orthodox early desert fathers. “But — he worked with us students! We respected and liked him very much. What a hardworking, quiet, kind, modest man. That whole glorious background! And to think he never told a word of it to us.”

“To you?” He laughed. “We didn’t breathe a word to anyone at the time. But in ’78 I flew to Leningrad from Moscow to see him in July, and take him to dinner. Little did he guess that I’d called on our whole collective for a reunion; they came in from all over. We surprised him with a festive ambush. He was lecturing that day, and we all burst in to the auditorium and ushered him away.”

“In the last week of July ’78,” I sat up in my chair. “On our last day of summer term, a whole group of men came in to the lecture hall and swept our administrator out the door. We students just thought it was his birthday. He looked very touched and happy to see his friends. It was an important occasion; one of the men even brought in a splendid tall bouquet.”

“With 35 flowers.” He smacked his hands together. “One for each year.”

“Roses in red, white, and gold.”

“Red, white and gold! The banner colors of our mission!” He beamed at me. “You can’t imagine how much work it was to obtain all those roses and carry them around town.”

“The one with the roses was you?”

“Naturally, I was younger then. My hair was red, not gray.”

“Mine was redder instead of gray too,” I laughed. “And all of us were younger.” Amazing; my companion’s presence in this room was the only remnant of a treasured memory from that week. He and his roses were the incidental backdrop, like black velvet for a gem under glass.

In July 1978, after that last lecture on that last day of class before our return to America I left campus for a social invitation to the historic district of Nevsky Prospekt. There a remarkable Old Petersburg family welcomed me in and talked to me over tea. The young man of the family was off in the corner behind the grand piano, ostensibly studying a Rachmaninoff score. But all during my teatime interactions with the family he watched me in silent wide-eyed intensity, as if he were upset by my visit. As it turned out, he was not upset at all.

“So what do you say?” Mr. Petrov leaned close. “How about it?”

“Sorry?” I was still rapt by that lovely reverie. The thought of that young pianist resurrected a long-buried fresh green tendril blooming in my heart, all hope and warmth and remembered kindness.

“There are things a woman can do. Your hair, for starters. What age did it turn gray?”

“My hair?” What in the world…? “Early. Age 17 or so.”

“High time to do something about it. And some cosmetics while you’re at it. Lipstick at least.”

“Mm.” My spirits had a long way to fall, back to reality and cramped yellow walls and this man who like many other patients harped about my hair, my shoes, my makeup, my clothes, and the bags that I carried. I stood up and headed to the door. “Would you excuse me a moment? I need to report in.”

“Interpreting,” said Maura. “What language?”

“Maura? Mary,” I whispered. “Has Cardio called you with any updates? No one’s around.”

“Schmidt’s deciding what tests to run. Keller’s behind the scenes saving everybody’s bacon.”

“Interpreter!” Nurse Keller came up behind me. “Stop discussing cases in the hall.”

“That’s her now,” said Maura. “When that nurse says Jump, do not stop to ask how high.”

“Get back to your post.” said Nurse Keller.

“Yes, Ma’am.” I hung up.

“And I am not your Ma’am,” she blazed up. “My title is Nurse!”

“Yes, Nurse Keller.” I headed back to the room, leaving the door open.

Mr. Petrov sat examining my appearance. “Yes, it’s time to do something about that hair. You’re not exactly 17 any more. At your age now, you must be a full Professor.”

“Full professor?” Anyone in the American work force would find it strange to think that a contract interpreter would have full professor rank. But the question was truly odd coming from the educated elite of the Soviet Union, a system where professors had such prestige that their apartment buildings even bore engraved bronze plaques, to inform passersby that an academic had lived there! “Full professor? Why, no.”

“You’re not a full professor? But you did complete your doctorate, didn’t you?” he persisted.

“Doctorate?” This was another offbeat question. A Soviet doctorate meant much more than completion of a course of study and research. The title indicated exceptional innovative achievement in a specialty field. “But the interpreting career is not an academic track,” I explained. “For hospital work, I am fully qualified. We pass written and oral state exams and hiring interviews; we take continuing education courses with constant training and observation on the job, regular assessments, and shadowing opportunities. Our training never ends.”

“But for Russian language — don’t you have an academic background?”

“I do, in Russian language and pedagogy. All the coursework needed for a doctorate.”

“But did you finish?” Mr. Petrov didn’t miss a beat. “The doctoral degree?”

“Mr. Petrov.” I resorted to a courteous fallback phrase. “Interpreter is here to focus on you and on your health. If you have any questions for the team, or –“

“Did you finish your doctorate?”

“I don’t know of any doctorate in medical interpreting. I’m certified with the department of health.”

“Did you finish your doctorate?”

“Do you have concerns about our training process? You are welcome to contact my supervisor. Dispatcher Maura, our lead Russian interpreter, can describe the process for you, so that –“

“Did you finish your doctorate?”

“No, Mr. Petrov.” That was certainly not a secret. But that academic ordeal in graduate school was still a source of deep regret. It ended the dream of an academic career, and work and research opportunities here and in Russia. “It’s a different path,” I assured him. “I earned a second Masters in teaching English to speakers of other languages. I taught vocational English to newly arrived Russian speakers. It was good meaningful work.”

“So you’re a letún,” he concluded. The root is letát,’ meaning to fly here and there. To the wartime generation, anyone who changed careers was seen as unfocused, unreliable, lacking in integrity. “And now you’re trying out yet another career! Practicing on us patients.”

“Mr. Petrov.” I took a deep breath. Interpreter Rule: Focus the patient on the visit. “The team will be here soon. Let’s turn our attention to anything you might like to say to them.”

Cardiologist Schmidt and the EKG technician hurried in for a second EKG exam. Again I squeezed into the corner with my nose to the wall. As they examined the results and left, Dr. closed the door a little harder than necessary.

“Not a full professor.” Mr. Petrov gripped the arms of his chair. ” No dissertation. Yet you take human lives in your hands and on your conscience every day!”

“Whatever concerns you would like to report to the team or to anyone else, let me know how I can assist. I’m right here.” I cracked open the door and stood there. Interpreter Rule: When a conversation becomes emotional and off topic, do not remain unchaperoned with the door closed. During an extended wait, part of an interpreter’s job was to moderate the conversational dynamics, to keep the patient calm and in place, ready when the provider showed up.

“Interpreter.” Nurse Keller summoned me out to the hall. “For HIPAA confidentiality, you are to keep that door closed at all times. You are to stay inside that room and with your patient. If you open the door and wander out here one more time I swear I will write you up.”

I stepped back inside. She closed the door.

Mr. Petrov paced the room. “How many CHILDREN do you have?” he fired off.

“Excuse me?” Now I was uneasy. There was a real change in his manner and mood.

“It’s not a complex question.” He sounded anxious and irritable. “Think.”

“I don’t have any.”

“Who knows how you arranged that?” He looked me over. “So. If you haven’t raised a child, what makes you think that you can take care of patients?”

To be fair, that was the standard get-acquainted question. Patients across many culture groups believed that female interpreters were better at patient care if they were also wives and mothers. Interpreter Rule: As with any hazing ritual, the key was to remain serene and well-intentioned, letting the comments drift past. If we interpreters showed the slightest sign that we felt hurt or taken aback, our questioners would conclude that they had hit upon some interesting secret. They would probe even harder, then spread their speculations to the other patients.

Now I steeled myself for the central question: marital status. Patients got around to that one sooner or later, usually sooner. Next they would warn me that single women have unbalanced hormones and become emotionally unstable. (Popular stereotypes about this abound. At minute 1 hour 36 of the 1980 rom-com Moskvá slezám ne vérit, or “Moscow Does Not Believe in Tears,” the hero’s very first come-on overture line to the heroine is that she has the glance of an unmarried woman — “Otsénivaiushchii, kak smótriat militsionéry,” searching and appraising, like that of the police.) At one of my other hospitals, a Russian supervisor tried nagging me to go out on the weekends for drinking and a sex life: “If you dry out, you’ll be no use to our patients.” (This Russian vysókhshaia, or out + dried, is the ultimate criticism of a woman perceived as an old maid.) Back at that same hospital, a member of leadership would test the freshness of the female interpreters by lining up the women every Monday to collect from each one “a kiss for Papa.” As the new employee I offered him a handshake instead. The look he gave me signalled that my days in that department were already numbered.

As if on cue Mr. Petrov asked “Are you at least married with a husband?”

“No.” My eyes tuned out the room, gazing far into the distance past the yellow walls.

“And why is that, tell me?”

“Bózh’ia vólia. God’s will.”

“God’s WILL.” It was a crooning simper, treacle and brimstone. “So you failed at that too.”

Everything went blank. The meaning of everything was suspended: time, space, the little green tendril of hope, the yellow walls, English, Russian. It dawned on me: being alone was not a dark valley to walk through with patience and courage to the other side, not a process of more personal growth and social skills, not just a vocation to marriage ready and waiting if only I prayed long enough and let go and let God, not just some one ingredient lacking in whatever I’d done so far in life. No, being alone came from my own deep identity. The fault was not what I did, but who I was. It was not that life had failed me, but that I had failed God Himself and failed the lifetime population of available solid single men that He created. And I wasn’t good enough for any of them.

Somewhere deep in me a finely tuned mechanism, a biological clock held in perfect readiness and fueled by a lifetime force of faith and hope, snapped its mainspring and died for good. I had no idea how much that clock had kept me going through the years until now when it was gone.

In self-defense, I almost told Mr. Petrov everything: about the Old Petersburg family with their delight in my visit, their ancient monogrammed silver and remaining teacups and their stories of the past, about the Conservatory student behind his grand piano who gazed at me the whole time, simply because he thought I was beautiful and gentle and good, how that young man then spent my last week in town showing me his city, and how at every greeting and goodbye he bowed low and kissed my hand. But my words to Mr. Petrov were stopped by some deep intuition. Tell him nothing; not a word it seemed to say, as if my own guardian angel with a double-edged sword were shielding the silence of my little Eden.

Interpreter Rule: Keep your mind on the job. The summer of ’78 was gone, and no man was going to bow to me and kiss my hand like that again. I sat up straight, gripping to my chest my vocabulary collection binder, with fingers marking tabbed section 7 (Cardiology: anatomy, physiology, testing, medical conditions). The door flew open. The team filed in: Medical Assistant Cassie, the EKG technician, Nurse Keller, Cardiologist Schmidt, and with them a matronly woman with a calming tuneful voice. Their interpreting appointment began in earnest. But the cosmic clockwork that powered the meaning of life had just died. There was no human left sitting in my chair, gripping a binder of vocabulary and packed bags and a head full of rules. The Interpreter had left the room.

Everyone stared at me as I sat stunned and gaping at the yellow walls.

Then, from the depths of auditory recollection, another personality stepped in took over. She was the voice of Radio Leningrad, the Díktor at the microphone, switching on at 6:00 am right after the national anthem, taking charge of airwaves on each radio all over the city. She was poise and style and even-keeled clear diction, declaiming the news from a government that handed down all the answers. She took me over like a fist in a puppet, commanding Russian conjugations, declensions, perfective and imperfective aspect, determinate and indeterminate verbs of motion, the dictionary terms pored over for those state exams, and years of interpreting for everybody else. Every time the care team began an English sentence, The Voice saw the end of that sentence coming. She formulated the Russian simultaneous reply, and muscled it right back.

Hello! Can you tell us your name?

And how are you feeling today, Mr. Petrov?

Can you tell us where you are, and why? What is today’s date?

You had a pacemaker check the first of the month, two weeks ago? How have you felt since then?

Who is the President? (“Yours or mine?” Mr. Petrov sassed them back, and named them both.)

Can you count backwards from 100 by sevens? Well. That was fast.

Would you show us all your medications again? Can you tell us what each one is for? Have you taken each one as directed? Has the dosage changed? Let’s compare each one with the medication list on your patient chart. Is your pharmacy still the same, for refills?

Has your insurance changed?

In the past two weeks, have you changed your diet, sleep, exercise?

In the past two weeks, has your vision changed?

In the past two weeks, has your breathing changed? What about bowel or bladder habits?

Do you smoke?

Any family history of cardiovascular ailments?

Can you cross the room along that straight line, please?

Can you count many fingers I am holding up?

Can you hold your arm out, and then sweep your hand in and touch your nose?

Are you left-handed, or right-handed? (Interpreter Rule: raise hand, and ask permission to speak. “Interpreter would like to mention that in the Soviet Union all children were trained to use only their right hand for penmanship. The hand used for writing may not be the dominant hand.”)

Are you allergic to any medications?

Are you allergic to any medications, or substances including latex?

Do you have difficulties with general anesthesia? Do you have any chipped or broken teeth?

Do you feel safe at home?

Are you afraid of falling? (Mr. Petrov laughed outright. Men on The Mission were not, to put it mildly, afraid of falling.)

Is your son still your emergency contact?

Do you ever think of harming yourself?

Are you concerned about your level of drinking?

Do you ever feel that someone is listening in on your phone calls, or your private conversations in your home? (“Interpreter requests permission to speak. In some cultural settings, it is routine for phone calls and home conversations to be monitored by a third party.”)

Have you lost interest in any favorite activities including sex?

The action then proceeded from room to room, starting with the Blood Draw lab. Mr. Petrov refused a wheelchair with a head toss of contempt until Nurse Keller looked up at him. He sat down then.

“Nurse Keller? At some point I will need to call Base,” I ventured, on one of our transfers.

“I called,” she said, taking a turn with the wheelchair.

“For Rodion at 8:00 tomorrow?”

“Maura’s got it,” she said.

“And Pineview Manor? Reserving their shuttle for tonight and tomorrow –“

“Told ’em.” She gave me a collegial nod.

The energy of the team was attentive and non-committal. Mr. Petrov’s interest had long worn off; he was like a cultured talk show host grown weary of the guests: the schoolboy with trite magic tricks, or the zoo visitor displaying a contrary animal, or in this case the smiling tuneful-voiced woman who introduced herself as a social worker and asked gently whether Mr. Petrov had an Advance Directive on file?

No, Mr. Petrov did not. Granted, in a perfect world, advance directives were supposed to be handled sooner, during routine visits with a trusted primary care provider, long before they were needed. They were not meant to be an afterthought during a health crisis or en route to the OR. But that is exactly when they usually come up in conversation. The topic was never popular. Patients assumed that we were questioning God’s will, tempting fate, securing permission to turn off life support, or trying to frighten the chronic Medicaid patients into an earlier death.

The social worker then asked with special gentleness whether in his culture Mr. Petrov had any special Spiritual Needs.

Mr. Petrov looked to me. “Shto? What?”

I interpreted and paraphrased the question three times.

“Spiritual needs? No.” He flashed his teeth in a defiant laugh, reminding me of Beethoven shaking his dying fist at the thundering sky.

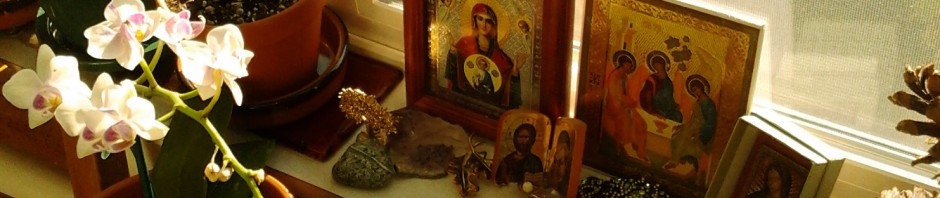

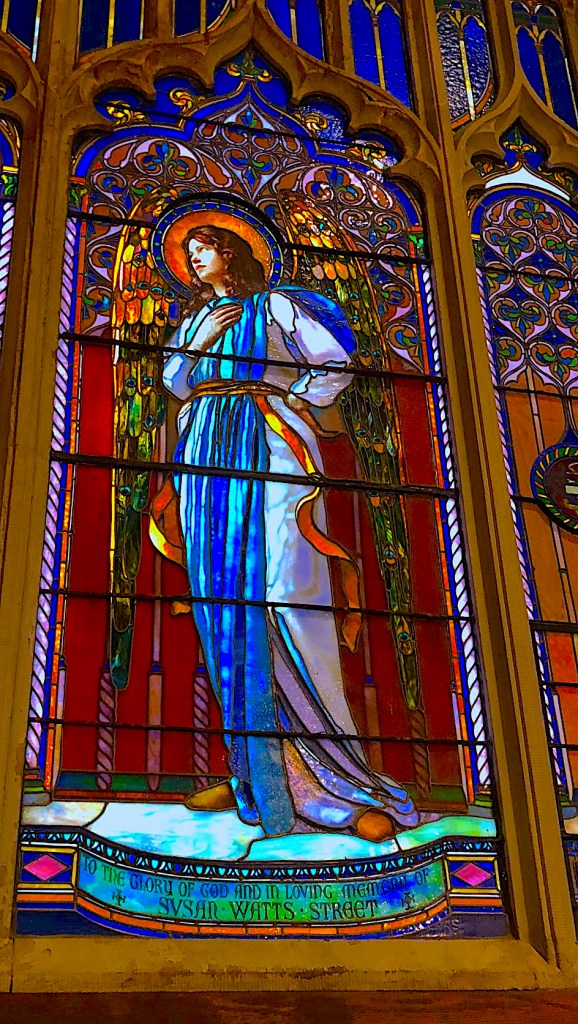

For the next couple of hours, my Radio Voice continued to speak for me and to animate energy in my steps and steel in my spine. There were only three strange side effects. One, my hands trembled with adrenalin and the ambient electricity of the medical drama around us. Two, my eyes absolutely refused to look at Mr. Petrov, to reveal to him any more of the mirror of my soul. Three, these eyes overflowed with tears. Despite the calm dispatch and demeanor of the best interpreting work of my entire life, the tears flowed on their own. The effect called to mind accounts of the Orthodox Christian experience of the Chudotvórnaia Ikóna, documented wonder-working icons, where a depicted saint mysteriously sheds myrrh-bearing tears of fragrant chrism, gathered by the faithful to heal the sick and the broken of heart.

And all the while, Mr. Petrov kept up his sotto voce comments in my direction. “It’s obvious you’ve never been married,” he hissed at me. “Why would you care for a husband? When you met a patient late, without checking his chart? No lipstick, no makeup. No proper name on your badge. Squatting in one room like a bohemian, not at home caring for your parents. Didn’t bother to finish school. Thinks that literature is tales about a cancer ward by some muck-raking literary hack! Rákovyi Kórpus indeed.”

Because the patient addressed none of this to the providers, and because the providers had nothing further to say to the patient, there was at last nothing more to interpret. The team agreed to reconvene at 8:00 am with Mr. Petrov and Interpreter Rodion for more testing. They dispersed for the night. I ran back to the exam room and fetched the leather satchel from the hook on the door, then ran to catch up with the group as they headed out of Cardiology. “In only fourteen days!” Schmidt’s voice faded down the hall. “…the hell could have happened?”

Mr. Petrov packed up his patient visit summary printout. “American success. Career before love and family. You aren’t here for the patients. You’re here for the pay.”

“Here is your bag, Mr. Petrov. Reception is this way.” Still drying my eyes I handed Mr. Petrov his leather satchel, and pointed him back in the right direction.

“You don’t know what it is,” he shook his head. “To love a man. With all your heart.”

Through my tears a haze of red and glitter swam into view, from a display window of flowers and balloons. The Gift Shop was closed. Valentine’s Day was over.

“Vot smotríte. Just look at yourself,” Mr. Petrov marched past the shop. “You are acting like a child! You deliberately chose to misunderstand my intentions.”

“Evening, Dotty,” I greeted the night Receptionist. “One for Pineview Manor.”

“Driver’s right there.” She slid the transport book across the counter.

“Great.” I checked off Mr. Petrov’s name from the list of patients expecting rides, wrote in the departure time, and dried my eyes. “Good evening!” I hailed the driver.

“How are ya,” the driver greeted me. “Hiya, Nick!” He led us to the green and white shuttle.

“Sovétoval kak drúg.” Our passenger fastened his seat belt. “I advised you as a friend. For your own good. You don’t have the constitutional fortitude to face the truth about yourself.”

“All set?” I checked that Mr. Petrov’s leather satchel was on his lap, and his hands and feet safely out of the way.

“Well ‘MARY.’ Or whatever your real name is,” Mr. Petrov concluded, “You can take off that badge now; you’re a professional disgrace. And the worst is, you can’t be bothered to care.”

“We’re ready!” I closed the door, waved to the driver, and stepped back.

I turned away with a deep yawning sigh of relief. But then in the darkness someone behind me seized my wrist. I gasped and spun around. A man bowed and kissed my hand, and sprinted back to a green and white van. The van pulled out. Its taillights splintered in red rays through the first raindrops in my eyes.

“Perevódchitsa — Vy opozdáli! Interpreter — You were late!” Mrs. Nina Melnik was part of the crowd heading home. “I expected you to show up for Radiology at 3:00. You kept us all waiting!”

“Your 3:00 interpreter was Zoya, she had to drive to get here,” I called over to her. “For 3:00 they dispatched me to a different clinic. I had to stay with the patient.”

“Well, it still delayed everyone. I wish you’d all organize yourselves and show up on time.” (Small Epilogue: Two years later, an email from Management notified me that on the contractor list my place had to be reassigned to a new interpreter for our many new speakers of Iraqi Arabic. I was hired instead by that same Radiology department. Mrs. Melnik was one of the patients who praised me once I was gone. “I’ll have you know,” she told Interpreter Zoya, “That Mary? She was a nachítannaia dévushka, a well-read girl. She knew not only her own literature, but she’d read ours as well.”)

“Polkáaan — domói!” Mr. Levitskii with his seat walker and his oxygen tank was boarding his Medicaid shuttle with his swollen legs and labored breaths and eager grin. “Fido — Go home!” he hollered as the driver fastened his belt. I gave him a snappy salute.

Before the two-mile walk home, in an alcove between two brick walls and the smokers’ bench, I sat down to put on my sweatshirt and scarf and boots and rain tarp slicker. Then I pulled the hood of the tarp low and rested against a warm heating grate to eat a banana. The bricks formed a little grotto all around, lined with wintering ivy. “Vysókhshaia,” I whispered in sympathy, reaching out to touch its leathery leaves. Its suction disk rootlets wrapped around my fingers.

A young woman with a cigarette came and sat down, hunching over in the chill. She wore a red knitted stocking cap and a fluffy sweater with red hearts.

“Oh.” I took a closer look. “Nurse Keller. Good evening.”

“Jesus! You scared me to death.” She nearly dropped her lighter. “Who is that?”

“Interpreter.” I pulled back my hood. “Thank you for all your help in Cardiology today.”

She sat, taking a long drag of her cigarette. “Why didn’t you go to nursing school?”

“Me?” My imagination took wing for a moment, then came back to earth. “Can’t handle stress.”

“Huh. So much for that then,” she laughed, standing up with car keys in hand. “Night, Hon.”

Pinpoints of precipitation whispered along my tarp hood. My eyes closed. A long-ago letter floated to mind, fountain pen ink in beautiful shaded Cyrillic letters.

Since you left here I’ve learned a number of pieces for piano, and progressed a great deal in technical execution; but the playing has gone dry, with a “touch of chill.” For my professor I played Rachmaninoff’s preludes in D Minor and B Minor. He was not pleased. “No lyricism,” he shouted. “Go fall in love with a girl!” In response I had only a hapless smile. And what lay behind that smile, only I knew. Well, and you. Yes?

He practiced so hard. He cared so much. And already his Rákovyi Kórpus was waiting for him.

My eyes blinked open in a soft glow of light. Someone at the hospital must have switched on a Gobo, a go-between optic light display, against the opposite brick wall. I’d only seen them outside city taverns, but now to my amazement the lighting cast a life-size image of the Vladimir Icon of the Mother of God. The wind rippled through her veil, setting the gems in her diadem to sparkle and gleam. Cradling the infant Jesus in her arms she gazed at me in sorrow and sympathy, with her eyes brimming with tears. Chudotvórnaia Ikóna! I sprang to my feet for a closer look. But the tears of Our Lady were only crystals of sleet; her gown and veil were the wind on rippling ivy. The apparition disappeared. My own tears calmed down and stopped.

________

7:15. At Base I checked the mailbox. Schedules were ready, but none was printed for me. In the staff room, at the Chinese language station, the interpreters kept a little memorial temple, a wooden model with a tiny ceramic bud vase with a single flower. Tonight in the temple window there was a new light from a battery candle. Inside the temple door there was a new rice paper scroll with some Chinese calligraphy. “Good bye, Mr. Scotty,” I whispered. “Sleep in peace.”

In the dispatchers’ office, the lights were on. Lead Interpreter Maura always started in at 6:00 am, an hour before her shift, to walk the wards and check on our patients who needed care most. Now she was still here, after hours. She was keying numbers on an adding machine, leafing through a tall stack of crumpled appointment schedules.

“You’re still here!” I greeted her, hanging my slicker outside the office door. “Mr. Levitskii was outside just now; still in rare form, whistling for us dogs.”

“He’s on his last legs,” Maura said softly. “Your schedule’s late. Short month. They’re due the 14th. I’ve already totaled up the batch.”

“Oh. Sorry.” I unfolded my schedule on her desk. “We ran way past 5:00.”

“You know the rules. You tell the clinic to fax it to us by 6:00!”

“Stella was long gone. And there was a lot going on.”

“Look here: They didn’t sign you out! How am I supposed to submit this? Accounting won’t pay. Take that schedule right back to Cardio tomorrow. See if you can talk them into signing for next pay period. I’d sign myself, but when a timesheet’s overdue, Payroll might audit us.”

“Anesthesiologist to NICU, stat!” A woman’s voice broke in on the overhead, broadcasting full volume. “Anesthesiologist to NICU, stat! Anesthesiologist to NICU stat.”

“Okay,” I said. “Oh, Cardio for 8:00 tomorrow morning. Did Cassie call? Petrov has tests.”

“Keller called. And he doesn’t.”

“Ya he does. They want him back in the morning.”

“They’ve got him now.”

“Petrov? He’s gone home. I just saw him on the Pineview shuttle myself.”

“He passed out in the van. Shuttle driver brought him to the ER.” Maura hit the print key.

“He was fine not an hour ago! Will he be okay? Was it his heart?”

“Stroke.” Maura tore off the adding machine tape roll.

I squared my shoulders. “So… do you need me to stay tonight? Interpret for him?”

“Cancel anesthesiologist to NICU,” said the woman in the ceiling. She sounded tired. “Cancel NICU.”

“Not much point interpreting. Not if he’s unconscious.” She stapled the roll to the timesheets.

“For his wife Lilya, though. Whatever she has to say.”

“Oh very funny,” she seethed at me. “Is that your idea of a joke? What is that supposed to mean?”

I noticed her bloodshot eyes and the catch in her voice. “Nothing. I don’t mean a thing. Night.” I collected my slicker and turned to go.

“Wait.” Maura stood up. In her eyes the flash of indignation faded to dismay. “But you’re the last person he spoke to! Didn’t you — He must have — All that time, what did he talk about?”

“Talk? About 1943, what else.” I took off my lanyard and photo ID. “Being a hero.”

Maura sank back to her chair and took off her glasses. “She’s dead.”

“KELLER?” I put down my bags.

“No. One of those missed voicemails was Pineview Manor. Lilya died last week. She had leukemia for years. Nikolai took care of her.” Maura put her glasses back on. “Look, just gimme the timesheet. I’m signing you out myself for 7:30. That’s walking Petrov to the shuttle, and to make up for the lunch break you didn’t get.” Maura knew the rules: on-call interpreters don’t get a paid lunch. But she made the change anyway.

“Thank you, Maura. I’m very sorry to hear this. Inseparable, weren’t they?”

Maura signed my timesheet, stapled it to the batch, edited the paper tape, and bundled it all in a string-cord envelope. “Your schedule’s in the printer. Surgery Prep is at 6:45 tomorrow morning. Check in there at 6:30.” She turned back to the answering machine, and hit Play.

I picked up my bags.